Report on policy support for e-Procurement Version 1.0 (The Landscaping Document)

- 1. INTRODUCTION

- 2. PROCESS, METHODOLOGY, AND TECHNOLOGY

- 3. TARGET AUDIENCE & USE CASES

- 4. RELATED ONTOLOGIES/VOCABULARIES AND PROJECTS

- 5. CONCLUSION AND NEXT STEPS

- 6. REFERENCES

Document Metadata

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

Date |

2016-09-20 |

Status |

Accepted |

Version |

1.00 |

Authors |

Nikolaos Loutas – PwC EU Services Brecht Wyns – PwC EU Services Stefanos Kotoglou – PwC EU Services Dimitrios Hytiroglou – PwC EU Services |

Reviewed by |

Pieter Breyne – PwC EU Services Natalie Muric – Publications Office Cecile Guasch – European Commission, DG DIGIT Vassilios Peristeras – European Commission, ISA Programme |

Approved by |

Natalie Muric – Publications Office |

This study was prepared for the ISA Programme by:

PwC EU Services

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this report are purely those of the authors and may not, in any circumstances, be interpreted as stating an official position of the European Commission. The European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the information included in this study, nor does it accept any responsibility for any use thereof. Reference herein to any specific products, specifications, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favouring by the European Commission. All care has been taken by the author to ensure that s/he has obtained, where necessary, permission to use any parts of manuscripts including illustrations, maps, and graphs, on which intellectual property rights already exist from the titular holder(s) of such rights or from her/his or their legal representative.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Context

Public procurement represents around the 20% of GDP in Europe. This big buying volume offers a high economic potential to enhance efficiency of European procurement.

The EU is investing significantly on the digitalisation of the public procurement process (referred to as e-Procurement). This goes beyond simply moving to electronic tools; it rethinks various pre-award and post-award phases with the aim of making them simpler for businesses to participate in, and for the public sector to manage. It also allows for the integration of data-based approaches at various stages of the procurement process.

With e-Procurement, public spending should become more transparent, evidence-oriented, optimised, streamlined and integrated with market conditions. More specifically, e-Procurement offers a range of benefits such as:

-

significant savings for all parties, both businesses and the public sector;

-

simplified and shortened processes;

-

reductions in red-tape and administrative burdens;

-

increased transparency;

-

greater innovation;

-

new business opportunities by improving the access of all enterprises, including small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), to public procurement markets.

To deliver the aforementioned benefits, e-Procurement relies heavily on the exchange of data between the different systems supporting the procurement processes i.e., achieving end-to-end interoperability of public procurement processes and underlying systems, and on the availability and dissemination of procurement data to the wider public i.e., improving transparency and stimulating innovation and new business opportunities.

As stated in the Commission Regulation 2015/1986 (EU), contracting authorities in the EU are legally required to publish notices above certain capital thresholds. Article 6 of that Regulation states that either the online eNotices application or the TED eSender systems should be used for electronic transmition of notices to the Publications Office of the European Union. From a different angle, the implementation of the/ a revised PSI directive across the EU is calling for open, unobstructed access to public data to improve transparency, and to boost innovation, via the reuse of public data. Procurement data has been identified as data with a high-reuse potential. Making this data available in machine-readable formats, following on from the "data as a service" paradigm, is required to maximise its reuse.

Data exchange, access, and reuse are key requirements for efficient and transparent end-to-end public procurement. Because of this, we observe a shift in focus from the definition of procurement process standards for system-to-system exchange, to the development of data standards for publishing e-Procurement data in open, machine-readable formats (see Chapter 4 Related Ontologies/Vocabularies and Projects).

The key challenge is that procurement data exists in different systems across the European Union:

-

the relations between the different concepts in the procurement chain and data flow are not fully documented, therefore data and data relationships cannot be reused directly in a flexible and comparable manner;

-

some data has inherited formats from its paper origins leading to illogical business processes and incorrect conceptual models;

-

different systems use different data formats therefore reuse of information is not always efficient; and

-

taxonomies like CPV are often not used correctly which creates serious problems e.g., making it very difficult for SMEs to find suitable business opportunities.

Given the increasing importance of data standards for e-Procurement, a number of initiatives driven by the public sector, industry, and academia have been initiated in recent years. Some have grown organically, while others are the result of standardisation work. The vocabularies and the semantics that they introduce, the phases of public procurement that they cover, and the technologies that they use all differ. These differences hamper data interoperability and reuse. This creates the need for a common data standard for publishing procurement data, hence allowing data from different sources to be easily accessed and linked, and consequently reused. The e-Procurement ontology (henceforth referred to as the ePO) introduced by this study attempts to address this.

1.2. Proposed solution

The ultimate objective of the ePO is to deliver a common and agreed OWL ontology that will conceptualise, formally encode, and make available in an open, structured, and machine-readable format, data about public procurement. The ontology will cover the public procurement process from end to end, i.e. from notification, through tendering to awarding, ordering, invoicing and finally payment.

It is not the intention of the ePO to reinvent the wheel by redefining existing terms or processes, but rather to unify all existing practices, thus facilitating seamless exchange, access and reuse of data.

Process, Methodology and Technology discuss in detail the open process and methodology that will be followed for developing the ePO.

1.3. Scope

This report does not focus on creating the specifications of the ePO, neither in the form of a conceptual data model nor as an OWL ontology.

The scope is to put together the information necessary to proceed with the specification of the ePO, including a process and methodology to be followed for the development of the ePO. The following activities are in scope of this work:

-

Identify the target audience and the key use cases for the ePO;

-

Document and analyse existing initiatives to discover overlaps and gaps, and identify which ones to reuse, and with which ones to align;

-

Identify data and code lists that can be referenced by the ePO.

1.4. Structure of this document

This document is structured in several sections. After describing the context, scope and the proposed solution in section 1, section 2 proposes a process and methodology to be followed and the technology to be used for the development of an e-Procurement Ontology. Section 3 identifies the main stakeholders impacted by the ePO or that should be involved in its development. It then describes the possible use cases that the ePO aims to address. In section 4, relevant existing data models and code lists are identified and analysed. Section 4 also assesses the extent to which existing works could be reused in the ePO. Section 5 concludes the report and identifies the next steps to be taken for the further development of the e-Procurement Ontology.

1.5. Common working terminology

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

Public procurement |

The process by which public authorities, such as government departments or local authorities, purchase work, goods or services from companies [_1]. |

e-Procurement |

e-Procurement is the conduction of the procurement process by means enabled by the internet [_1]. |

Call for Tenders |

Procedure of asking for bids to be submitted for the awarding of a contract [_3]. |

Pre-award phase |

e-Procurement process phases occurring up-until the award of the contract (e-Notification, e-Access, e-Submission, e-Evaluation, e-Awarding) [_4]. |

Post-award phase |

Post-award phase e-Procurement process phases occurring after the award of the contract (e-Ordering, e-Invoicing, e-Payment) [_4]. |

Data standard |

A structural metadata specification that describes or defines other data [ISO111179]. Structural metadata indicates how compound objects are put together [NISO]. It can consist of among others data models, reference data, and identifier schemas [_5]. |

Data model |

A data model documents and organizes data, how it is stored and accessed, and the relationships among different types of data. The model may be abstract or concrete [_6]. |

Conceptual data model |

The conceptual model enables to understand the meaning of the data model. Generally, the conceptual data model is the most important. The conceptual model does not specify how properties and associations are technically represented . |

Ontology |

A formal naming and definition of the types, properties, and interrelationships of the entities that exist for a particular domain. In the context of this report, an ontology should be expressed in OWL as this is the format used by the Common Data Model of the TED Semantic Web Service, in which the ePO will be implemented. |

Approved by |

Natalie Muric – Publications Office |

2. PROCESS, METHODOLOGY, AND TECHNOLOGY

The ePO will be developed following the ISA process and methodology for developing semantic agreements [_7], which is an open consensus building process that engages a working group of experts. The process outlines the roles that the different actors in the process play, as summarised in Table 1, and the steps that need to be taken to set up the working group environment. Table 2 outlines the consensus building process that deliver the ePO.

2.1. Actors & roles

Actors & Roles

Reaching consensus

2.1.1. Working Group

The Working Group for building consensus on the eProcurement ontology is made up of the following actors

-

Chair(s): the Publications Office will appoint one or several, usually not more than two, chairs who are responsible for leading the meetings of the working group, for ensuring that the process and methodology specifications are followed and that consensus is reached within the working group.

-

Editor(s): one or several, usually not more than two, editors will be appointed, who are responsible for the operational work of defining and documenting the ePO.

-

Working group experts: besides the chairs and editors, the working group will mainly consist of experts who are contributing knowledge and expertise required for the specification of the ePO. Members of the following groups and communities will be invited to join the working group as experts:

-

Members of the multi-stakeholder expert group on eProcurement of DG GROW;

-

Staff working on eProcurement from national, regional and local administrations in the EU Member States;

-

Staff working on eProcurement from the EU institutions, including representatives of CEF Telecom and the Open Data Portal;

-

Members of the CEN TC 440 (Technical Committee on Electronic Public Procurement) and the CEN TC 434 (Technical Committee on Electronic Invoicing);

-

-

Members of the Core Vocabularies working groups;

-

Members of the OpenSpending network, publicspending.net, the Open Contracting Partnership and related initiatives;

-

Research and academia working on related initiatives (refer to Chapter 4 for an overview of related activities).

2.1.2. Review Group

A Review Group should be invited to provide an independent external review on the first full draft of the ePO. This will be done as part of the public comment period. The members of the Review Group will come from the same groups and communities as the members of the Working Group. Ideally, a member of the Working Group should not also be a member of the Review Group.

2.2. Process Overview

Process

Reaching consensus

-

Identify stakeholders (The Publications Office and a contractor)

-

Form the working group (The contractor in agreement with the Publications Office)

-

Identify chair(s) (The Publications Office with input from a contractor)

-

Identify editor(s) (The Publications Office).

-

Identify review group (Chair(s) and Editor(s))

-

Verify and secure IPR (Intellectual property rights) (The Publications Office and the contractor as necessary)

-

Establish working environment and culture (Chair(s) and Editor(s))

-

Publish drafts (Chair(s) and Editor(s))

-

Review drafts (Working Group experts)

-

Publish last call working draft (Chair(s) and Editor(s))

-

Review last call working draft (Review Group)

-

Gather evidence of acceptance (Chair(s) and Editor(s))

-

Submit for endorsement (The Publications Office)

Once steps 1 to 7 of the process listed above have been conducted, the Working Group can start its operational activities. Steps 8 and 9 in the process above – creating and reviewing drafts – are repeated to create the ePO specification iteratively. The technical methodology, describing the steps that must be undertaken in the development of a specification, is described in Table 3 below. Steps 5 and 6 in the methodology below, the creation of a conceptual data model, might require several iterations and drafts before consensus in the Working Group is reached. For the Chairs, editors and Working group to have a starting point (for points 1-3 below) the contractor will present a project charter, a more detailed analysis based on the report of the methodology to be used. This will include:

-

how to reach the formal OWL ontology,

-

the production of the conceptual model and information requirements

from the suggested use cases via

-

the reuse of existing data and services,

-

suggesting synergies with other working groups in the domain of open data and/or public procurement.

The working group will agree on the methodology to produce the deliverables, adding and removing use cases as necessary, whilst adapting the methodology as it sees fit.

2.3. Methodology overview

Methodology

Developing a specification

-

Review analysis of existing solutions (based on Chapter 4 of this report and analysis mentioned in paragraph above) (Editor(s) and Working Group)

-

Review analysis of existing data and services (Editor(s) and Working Group)

-

Define and agree on use cases (based on Chapter 3 and analysis mentioned in paragraph above) (Editor(s) and Working Group)

-

Define methodology to be used (see analysis mentioned in paragraph above)

-

Identify information requirements (Editor(s) and Working Group)

-

Identify a meaningful set of Core Concepts (Editor(s) and Working Group)

-

Define and agree on terminology and create a conceptual data model (Editor(s) and Working Group)

-

Define naming conventions (Editor(s) and Working Group)

-

Define identifier conventions (Editor(s) and Working Group)

-

Draft the namespace document (Editor(s))

-

Specify conformance criteria (Chair(s) and Editor(s))

-

Perform quality assurance (Chair(s))

There will be a number of technologies and tools used to create and underpin the ePO, the main of which are listed in Table 4: Overview of technology to be used below:

2.4. Overview of technology to be used

Technology & Tools

Creating a model

2.4.1. OWL DL

The OWL language is built upon the RDF standard. It is an ontology modelling language for describing RDF data. It allows for the strict definition of concepts and the complex relationships between them . The eProcurement Ontology should be expressed in OWL since the Common Data Model of the TED Semantic Web Service - in which the ePO will be implemented - is expressed in OWL.

3. TARGET AUDIENCE & USE CASES

3.1. Target audience

The target audience of the ePO is made up of the following groups of stakeholders:

-

Contracting authorities and entities, i.e. buyers, such as public administrations in the EU Member States or EU institutions;

-

Economic operators, i.e. suppliers of goods and services such as businesses, entrepreneurs and financial institutions;

-

Academia and researchers;

-

Media and journalists;

-

Auditors and regulators;

-

Members of parliaments at regional, national and EU level;

-

Standardisation organisations;

-

NGOs; and

-

Citizens

3.2. Use cases

The ePO is designed to meet specific needs of the aforementioned stakeholders. These needs are described in the use cases below. The use cases are organised around the following categories:

-

Transparency and monitoring

-

Innovation & value added services

-

Interconnection of public procurement systems

| 1 | Transparency and monitoring |

|---|---|

1.1 |

Public Understandability In order to facilitate the understandability of the public procurement process, the parties involved in procurement processes, as well as citizens, journalists, and regulators, should be able to access procurement data easily in a structured and machine-readable format. Many stakeholders aim at gaining a quick understanding of the information provided rather than performing an in-depth analysis of the published documentation. Currently, two main challenges exists. Firstly, data coming from different e-Procurement systems are often fragmented, reflecting the compatibility challenges between source systems. Second, the data is available in different formats and representations, which are not always consistent and interoperable, and are therefore hard to connect and interlink. By providing a common view over e-Procurement data, the ePO will allow providers of procurement data to link their data and make it available in ways which will be easier for the non-technical consumer to interpret and reuse, in order to create a complete view of the public procurement process. Example: A watchdog would like to understand how a public administration purchases goods and services. Their main goal is to understand the procedure and gain visibility of all the procedural steps. Procurement procedures often consist of complicated documents and processes, which are scattered on different platforms and websites, and are not always understood by the wide public. As all procurement data is now represented and made available using the ePO, the watchdog can easily combine data from different sources, thereby providing the context for understanding the information. Information requirements: In this case it is required that: * the ePO can model all documents that result from any phase of the procurement process; * the ePO can model all metadata about elements of the procurement process, such as participating entities. |

1.2 |

Data journalism The ever increasing amount of digitised information leads to new ways of producing and disseminating knowledge in society. Data journalism helps journalists to: * identify information; * understand complex information; * identify complex data deriving from different sources; and * create compelling stories (e.g. through data visualisation techniques) which can be easily communicated and understood by the wider public. By providing a common way to describe e-Procurement resources and data, the ePO will enable data journalists to identify, extract integrate and analyse relevant information coming from different sources. Example: A journalist in France is writing an article about the total number and volume (in Euro) of tenders in the domain of transportation by looking at different data sources in the country, and also by comparing the French data with data from neighbouring countries, such as Belgium and Spain. As all data has been modelled using the ePO, it is easy for the journalist to identify all the data that is related to procurement procedures and the resulting invoices. The journalist is then able to integrate and analyse the data related to transportation, and produce data visualisations based on the organisation and location data of the tenders. Information requirements: In this case, it is required that: * the ePO can model data about economic operators, such as businesses (names, locations, contact details etc.); * The ePO can model calls for tenders; * The ePO can model invoices, moreover, it requires core, not private or sensitive data, about invoices to be available as open data; * data from the ePO can be linked with procurement data from other countries' procurement systems. |

1.3 |

Monitor the money flow In order to obtain an exhaustive and unified view of the flow of public money, from tax collection and budget through to procurement and spending, e-Procurement data should be integrated with other datasets such as budget, spending and location data. A common ontology such as the ePO is necessary in order to interlink such datasets, and help with the creation of a unified view of the flow of public money. Example: A procurement watchdog is analysing the flow of public money over an interval of two years. Using the ePO as the common model for representing data allows the watchdog to find their way through the different sources that have to be consulted, e.g. budget dataset, calls for tender and procurement notices, and to interlink the data in order to identify the trails. Examples of the data to be interlinked by the watchdog, in order to discover the flow of money could be: * the value of the contract; * the name of the awarded tender; * the location of the awarded tender; and * the department of the public administration that awarded the tender. Information requirements: In this case it would be required that: * the ePO can model all procurement process data e.g. calls for tenders, notices etc.; * the ePO can model economic operator data e.g. name, location etc.; * the ePO can model contract data e.g. contract value; * the ePO can model exclusion criteria etc.; * the ePO can link to other datasets e.g. budget datasets, spending datasets, tax information datasets. |

1.4 |

Detect fraud and compliance with procurement criteria For assuring efficiency and transparency, and for detecting fraud and corruption in public administrations, EU institutions, and contracting authorities, rigorous audits of procurement need to take place. In order to improve and further automate the audit process, different data should be made available in structured, machine-readable formats so that different data sources can be referenced and integrated. The creation of the ePO will be a first step towards achieving such integration. Example: While auditing the evidence submitted by the tenderer who was awarded the contract, the auditor noticed that the supplier did not comply with the location criteria that were agreed during the signing of the contract. The collated payment evidence proved that by disregarding the initial agreement, the supplier had leased services from outside of the European Union to reduce the cost of the works. Publishing e-Procurement data in a structured, linked, and machine-readable format, allows the interconnection of data on transactions, criteria, contracts, and evidences from different sources, e.g. including BRIS and ECRIS, thus facilitating cross-checking and automated fraud detection. Information requirements: In this case it would be required that: * the ePO can model the evidence, the contract, the procurement criteria, including the location criteria; * the ePO can link its data to data in other datasets, such as procurement systems of different countries or the BRIS or ECRIS. |

1.5 |

Audit procurement process In order to monitor the correct use of funds it is necessary to cross-check data from different sources. In the case of public procurement, when the payment and invoice data is represented as linked data through the ePO, it is possible to link it with budget data. In this way one can check if the amounts resulting from the invoices do correspond to the initially budgeted amounts. Example: A governing body wants to make sure that no payment through public procurement on any specific category exceeds the agreed amount. For this, the government body can easily organise all the invoice data of all procurements by category, combine it with budget data, and cross-check if the numbers add up correctly. Information requirements: In this case it would be required that: * the ePO can model payments, contract terms; * the ePO can link this data with budget data. |

1.6 |

Cross-validate data from different parts of the procurement process Representing all phases of procurement in a linked data format can allow for better cross-validation of the data of any part of the process. Example: After a contract has been awarded to a specific tenderer a watchdog would like to check if the criteria for the awarding of the contract have been met. By having all parts of the process linked, the watchdog can by identifying the specific contract and immediately identify the tenderer and the criteria of the contract. Through linking this data with data about the tenderer from other sources, such as their financial data, they can double check if the tenderer does actually fulfil the requirements. Information requirements: In this example it would be required that: * the ePO can model the contract awarded, the criteria of the contract, the details of the supplier; * the ePO can link is data to data in other databases such as those containing financial data about businesses. |

ID |

2. Innovation & value added services |

2.1 |

Automated matchmaking of procured services and products with businesses Automated matchmaking of procured services and products with businesses Example: An economic operator requires more information in order to find and decide on a trade partner. The economic operator is able to identify the ideal candidates by displaying the names of winners in different products or services against the value/cost of said products or services. Representing e-Procurement data following an ontology and making it available in a machine-readable format facilitates the automated mapping between the provided data about the economic operators and that about the economic activities. Information requirements: In this case it would be required that: * the ePO can model economic operator’s details such as names, locations, contact details etc.; * the ePO can model procurement criteria; * the ePO can link the data of the ePO to data of other sources including material costs, labour costs etc. |

2.1 |

Automated validation of procurement criteria Economic operators that submit a tender are required to fulfil several criteria. In order for a contracting authority to automatically validate whether the criteria are met by an economic operator, data, both from the contracting authority’s and the economic operator’s side, should be cross-checked. In order to automate this process, both the data and the evaluation criteria should be made available in machine-readable formats. Example: An economic operator submits a tender to DG Informatics of the European Commission. The offer is written based on the criteria defined by the contracting authority in the tender specifications. Through the semi-automated validation of the tender, the economic operator is notified whether the tender meets the procurement requirements in terms of evidence required to check against financial and other exclusion criteria. if not, the tenderer is provided with a list of further evidence required to fulfil said criteria, and only after this submission does the process move on to the manual evaluation of technical requirements. Such preliminary automation allows for gains in speed and efficiency. Information requirements: In this example it would be required that: * the ePO can model tenders, notices, offers by tenderers, procurement criteria, evidence; * the ePO can model the relationship between offers and procurement criteria. |

2.3 |

Alerting services Contracting authorities announce and publish calls for tender to economic operators, citizens, and third parties. Through the use of alerting services, economic operators can be informed about published calls for tenders that match their profile. In order to automate alerting services, e-Procurement data such as tenders and information about economic operators should be machine processable, so they can be integrated, matched, and the right data delivered to the right person (depending on their subscription to the alerting services). Example: A Spanish public administration procures stationery and textbooks for the forthcoming year. The public administration publishes the call for tenders on an online platform. Since the call for tenders is published in a machine-readable format, following the structure of the ePO, third-party applications can process the call for tender and send alerts to interested parties in their client bases. Usually, such third party applications offer their clients the ability to define criteria they want to be automatically alerted on. Information requirements: In this example it would be required that: * the ePO can model the calls for tenders and the tender details. |

2.4 |

Data analytics on public procurement data Although data is available in vast amounts, businesses and public administrations often fail to manage these data efficiently and extract useful and qualitative information from them. Applying e-Procurement data analytics could be advantageous for economic operators, contacting authorities, and external parties such as journalists and watchdogs. Applying data analysis techniques to e-Procurement data allows stakeholders not only to understand public procurement better, but also to take better informed, evidence-based decisions. In order to fully exploit the potential data analytics in e-Procurement, data should be published in machine-readable formats, in which the ePO plays a major role, and (preferably) linked open data. Linked Data allows for flexible data integration over the Web; this helps to increase data quality and fosters the development of new services. Example: The European Commission aims to leverage its decision-making capability during a call for tenders in telecommunications by analysing all the data available about the potential suppliers and forecasting a fair market price. The European Commission aims at ensuring that the contract will be awarded to the supplier that provides the best services at the best price. In order for the European Commission to conduct its analysis, e-Procurement data should be integrated with a large amount of data coming from different sources, such as data about fees and pricing, qualifications, technical specifications, and cost of materials. Information requirements: In this example it would be required that: * the ePO can model economic operators and procurement criteria; * the ePO can link its data with that of other sources that provide data on fees, pricing, cost of materials etc. |

ID |

3. Interconnection of public procurement systems |

3.1 |

Increase cross-domain interoperability among Member States The European Union aims at providing a competitive economic environment for economic operators from different Member States. In order to achieve such a competitive environment, economic operators, public administrations, researchers, and academia should be able to access and exchange procurement information coming from different sources around Europe, allowing them to participate in calls for tenders from procurers from different Member States. Similarly, contracting authorities should be able to access information about economic operators, which are based in different Member States, and submit tenders for procured services. Making e-Procurement data available in common well-structured and machine-readable formats enhances cross-domain and trans-European competiveness by allowing economic operators from any Member State to participate in public procurement in any other Member State. Example: The VAT authority of a Member state wants to monitor the activity of a certain economic operator. By having all procurement data in all Member States published in a common and machine readable format, this data can be integrated into the systems of the VAT authority. This way it can instantly gain access to all data about any business conducted for public administrations by that economic operator in any other Member State. Information requirements: In this case it would be required that: * the ePO can model the whole procurement process and the details of each phase; * the ePO uses unique identifiers for the economic operators and contracting authorities and uses common reference data wherever required, such as NALs, NACE codes, CPV, common codes for products etc.; *the ePO can link its data to a dataset containing information about economic operators. In this example the VAT authority would simply have to gain access to the systems hosting procurement data of each Member State and it will instantly acquire all needed data. |

3.2 |

Introduce automated classification systems in public procurement systems During the procurement procedure, especially upon the receipt of offers, procurers receive many documents from different sources. Improved and automated classification of these documents would facilitate, and make more efficient, their processing and archiving. The ePO will set the grounds for common ways and rules for classifying such documents. Example: A contracting authority procuring agricultural products is receiving different types of documents and evidences from potential suppliers via its electronic submission platform. When uploading documents, suppliers are asked to complete core metadata coming from the ePO. For example, implementing the ePO facilitates the provision of the specifications of their products, the financial state and the contact details of the suppliers in a commonly agreed and structured way. The platform of the procurer can then automatically classify all received documentation, using machine learning techniques, based on different dimensions including, among others, the following: * The price of the tender; * The category of the tenderer’s business; and * The extent to which the tenderer complies with specific criteria. Information requirements: In this case it would be required: * Of the ePO to model all documents and evidences regarding tender offers; * Of the ePO to model procurement criteria; * Of the ePO to model details about the economic operators; * Of the ePO to model product categories. |

Table 5, Relevant actors for each use case, below summarises the relationships between the identified actors and the uses cases.

Use cases/Actors |

Contracting authorities |

Economic operators |

Academia |

Media/ journalists |

Auditors/ regulators |

Parliament |

Standardisation organisations |

NGOs |

Citizens |

1.1: Increase transparency and public understandability |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

1.2: Data journalism |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

1.3: Monitor the money flow |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

1.4: Detect fraud and compliance with procurement criteria |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||

1.5: Audit procurement process |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||

1.6: Cross-validate data from different parts of the procurement process |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||

2.1: Automated matchmaking of procured services, products and businesses |

x |

x |

|||||||

2.2: Automated validation of procurement criteria |

x |

x |

|||||||

2.3: Alerting services |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

2.4: Data analytics on public procurement data |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

3.1: Increase cross-domain interoperability among Member States |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

3.2: Introduce automated classification systems in public procurement systems |

x |

x |

4. RELATED ONTOLOGIES/VOCABULARIES AND PROJECTS

4.1. Data models and ontologies

4.1.1. CEN WS/BII business term vocabulary and semantic models

The CEN Workshop on business interoperability interfaces for public procurement in Europe (CEN WS/BII), established in March 2007, had the objective of providing a basic framework for technical interoperability in pan-European electronic transactions. It delivered a complete set of profiles covering both the pre-award and the post-award phases of the public procurement. The existence of these profiles and their associated semantic data models has been key in allowing disparate solutions to interoperate.

These profiles describe aspects throughout the whole procurement process such as notifications, the call for tenders, awarding and contracting. These profiles were implemented in several projects in Europe: the European Commission used them to build e-Prior, their open source solution for electronic invoicing and ordering, now also covering the pre-award phases; the PEPPOL community has also used them to create their own BIS specifications, resulting in a national-wide deployment of electronic invoicing in countries such as Norway, Denmark and Sweden, and other public administrations in Europe are currently basing their IT infrastructure and electronic procurement policies on deploying these standards e.g.,the National Health Service of the United Kingdom.

These profiles were updated in 2015 and examples of some profiles are listed below in Table 6 Examples of CEN BII Profiles.

| CWA | BII Profile | Transaction Information | UBL Syntax Binding |

|---|---|---|---|

CWA3456-119 |

BII54 Tendering |

Submit Tender |

CWA3456-218 |

Tender Receipt Notification |

CWA3456-205 |

||

CWA3456-112 |

BII47 Call for Tenders |

Call for Tenders |

CWA3456-212 |

CWA5678-104 |

BII06 Procurement |

Order |

CWA5678-301 |

Invoice |

CWA5678-305 |

||

CWA2345-101 |

BII10 Contract Notice |

Contract Notice |

CWA2345-201 |

These semantic models and their mappings to XML document exchange syntaxes, such as UBL and UN/CEFACT, should now be converted into knowledge to enable them to go a step further, by promoting a whole set of new functionalities such as searching for opportunities by sellers, comparing offers by buyers, getting statistical data, or improving the control and transparency in the electronic procurement procedures in the European Union.

In 2015, CEN established a new technical committee (TC) whose purpose is to develope standards to support and facilitate the electronic exchange of information in public procurement [_8]: CEN/TC 440. The technical committee will develop semantic data models, based on CEN/BII. TC/440 will closely collaborate with CEN/TC 434, a technical committee for the development of standards supporting European Electronic Invoicing [_9]. The work of CEN/TC 440 and TC 434 is closely related to the development of the ePO. Therefore synergies between CEN TC/440, TC 434 and the ePO should be developed as far as possible.

4.1.2. Open Contracting Data Standard

The Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) was developed for the Open Contracting Partnership (OCP) by the World Wide Web Foundation . The OCDS enables disclosure of data and documents at all stages of the contracting process by defining a common data model. It was created to support organizations to increase contracting transparency, and allow deeper analysis of contracting data by a wide range of users [_10].

The Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) is maintained using JSON Schema. Table 7 displays the main sections and common objects used in the schema.

Section |

Object |

Description |

Planning: Information from the planning phase of the contracting process. |

Budget |

The budget object has the following sub-elements: Source, id, description, amount, project, project ID and URI. |

Rationale |

The rationale for the procurement provided in free text |

|

Documents |

A list of documents related to the planning process |

|

Tender: The activities undertaken in order to enter into a contract. |

ID |

An identifier for this tender process |

Title |

Tender title |

|

Description |

Tender description |

|

Status |

Current status on of the tender (value from codelist) |

|

Items |

The goods and services to be purchased, broken into line items wherever possible. |

|

minValue |

The minimum estimated value of the procurement |

|

Value |

The total upper estimated value of the procurement |

|

procurementMethod |

Specify tendering method (value from codelist) |

|

ProcurementMethodRationale |

Rationale of procurement method |

|

awardCriteria |

Specifies the award criteria for the procurement (values from codelist) |

|

awardCriteriaDetails |

Any detailed or further information on the award or selection criteria |

|

submissionMethod |

Specify the method by which bids must be submitted (value from codelist) |

|

submissionMethodDetails |

Any detailed or further information on the submission method |

|

tenderPeriod |

The period when the tender is open for submissions |

|

enquiryPeriod |

The period during which enquiries may be made and answered |

|

hasEnquiries |

A Yes/No field to indicate whether enquiries were part of tender process |

|

eligibilityCriteria |

A description of any eligibility criteria for potential suppliers |

|

awardPeriod |

The date or period on which an award is anticipated to be made |

|

numberOfTenderers |

The amount (integer) of tenderers |

|

tenderers |

All entities who submit a tender |

|

procuringEntity |

The entity managing the procurement, which may be different from the buyer who is paying/using the items being procured. |

|

Documents |

All documents and attachments related to the tender, including any notices |

|

Amendment |

Amendment information |

|

Milestones |

A list of milestones associated with the tender |

|

Buyer: The buyer is the entity whose budget will be used to purchase the goods |

additionalIdentifiers |

Alternative identifiers of the buyer |

Name |

Name of the buyer |

|

Address |

Address of the buyer |

|

contactPoint |

Contact point within the buyer entity, such as an E-mail address or a person |

|

Awards: An award for the given procurement. There may be more than one award per contracting process |

Id |

The unique identifier for this award |

Title |

Award title |

|

Description |

Award description |

|

Status |

The current status of the award (value from codelist) |

|

Date |

The date on which a decision to award was taken |

|

Value |

The total value of this award |

|

Suppliers |

The suppliers awarded this award |

|

Items |

The goods and services awarded in this award, broken into line items where possible |

|

contractPeriod |

The period for which the contract has been awarded |

|

Documents |

All documents related to the award |

|

amendment |

Amendment Information |

|

Contracts: Information regarding the signed contract between the buyer and supplier(s) |

Id |

The unique identifier for this contract |

awardID |

The award ID against which this contract is being issued |

|

Title |

Contract title |

|

Description |

Contract description |

|

Status |

Current status of the contract (value from codelist) |

|

Period |

The start and end date of the contract |

|

Value |

The total value of the contract |

|

Items |

The goods, services, and any intangible outcomes in this contract |

|

dateSigned |

The date the contract was signed |

|

Documents |

All documents and attachments related to the contract |

|

Implementation |

Implementation Information related to the implementation of the contract in accordance with the obligations laid out therein. |

|

Amendment |

Amendment information |

|

Language: Specifies the default language of the data |

The Open Contracting Data Standard cannot be directly reused in the ePO, because it is not an RDF vocabulary. It can however be used as an insight into all things that need considering during the modelling process as it is neatly structured and quite extensive. How it has developed its buyer URI could be analysed more in-depth.

4.1.3. Universal Business Language

Universal Business Language (UBL) has been designated by the European Commission as one of the first consortium standards officially eligible for referencing in tenders from Public Administrations and is freely available to everyone without legal encumbrance or licensing fees.

UBL is the result of an international effort to define a royalty-free library of standard electronic XML business documents, such as purchase orders and invoices.It is designed to plug into existing legal, business, auditing, and records management practices, eliminating the re-keying of data in existing fax and paper-based supply chains and being an entry point into e-commerce for SMEs [_12]. It is also used by nations around the world for implementing cross-border transactions related to sourcing (e.g. tendering), procurement (e.g. electronic invoicing), replenishment (e.g. managed inventory) and transportation (e.g. waybills and status).

The standard is the foundation for several European Public Procurement frameworks, including EHF (Norway) , Svefaktura (Sweden) , OIOUBL (Denmark) , e-Prior (European Commission DIGIT) , and PEPPOL [_13].

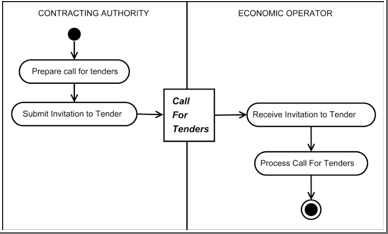

Universal Business Language provides a list of business objects expressed as reusable data components (e.g. address and payment) and common business documents (e.g. order and invoice), schemas for reusable data components and schemas for reusable business documents. Business objects from UBL that relate to the procurement field, include Invitation for Tender, Submission of Qualification Information and Awarding of Tenders. UBL Document Schemas related to e-Procurement include, for example, Call for Tenders. An example of these objects and how the relate, is described below.

Example

Business Object: Invitation to Tender

In this Business Object, i.e. the Invitation to Tender process, the Document Schema Call for Tenders is used. The Call for Tenders Document Schema is described as follows:

Document Schema Call for Tenders

Description: A document used by a Contracting Party to define a procurement project to buy goods, services, or works during a specified period.

| Processes involved | Tendering |

|---|---|

Submitter role |

Contracting Authority |

Receiver role |

Tenderer |

Normative schema |

|

Runtime schema |

|

RELAX NG schema |

|

Document model (ODF) |

|

Document model (Excel) |

|

Document model (UML) |

link no longer valid |

Summary report |

Since the UBL is the basis for many e-Procurement systems, as described above, it is considered a well-established standard. Therefore, it cannot be neglected when developing the ePO. Especially the UBL concepts related to procurement, such as invitation for tenders, call for tenders, etc. should be carefully looked into.

4.1.4. The European Single Procurement Document

In January 2016, the European Commission adopted the European Single Procurement Document (ESPD) , a document that aims to considerably reduce the administrative burden for companies, in particular SMEs who want to have a fair chance at winning a public contract.

To achieve this the ESPD maps out and replaces equivalent certificates issued by local public authorities or third parties involved in the procurement process, which can differ drastically between Member States.

While some countries have already introduced some form of “self-declaration” of suitability, others require all interested parties to provide full documentary evidence of their suitability, financial status and abilities. The ESPD will allow businesses to electronically self-declare that they meet the necessary regulatory criteria or commercial capability requirements, and only the winning company will need to submit all the documentation proving that it qualifies for the contract [_14].

To make full use of the ESPD concept, the European Commission will establish a service available for both suppliers and buyers, developing and providing the ESPD service free of charge to Member States and European Institutions. It will be provided as open source, so it can be implemented by service providers for their own use and to provide added value to buyers and suppliers [_15].

With regard to technical requirements, the transmission will be done through e-Tendering solutions. As the service works in conjunction with e-Certis, business registers and e-Tendering solutions, great care will be taken to harmonise the semantic data model. Development will be linked to e-SENS, the standardisation initiatives of CEN, the ISA Core Business Vocabulary, and solution providers.

In conclusion, the main objective of the ESPD is to reduce the administrative burden for buyers and suppliers participating in public procurement procedures. The ESPD service will reduce that burden by removing the need to produce a substantial number of certificates and documentation related to exclusion and selection criteria.

The ESPD initiative is worth examining carefully. As it maps all the certificates and evidence needed for procurement in the different Member States, it does the ePO a great service, as this is a task that will be necessary during the creation of the ePO.

4.2. CEN Core Invoice

Directive 2014/55/EU on electronic invoicing in public procurement states that Member States should ensure that contracting authorities and contracting entities receive and process invoices electronically. The European Commission tasked CEN, the European Committee for Standardisation, with developing a standard semantic data model, including business terms and rules, representing the core content of an e-invoice. The development in CEN is based on the CENBII Core Invoice data model and takes other international standards into account [_17]. Member States shall adopt, publish and apply the laws, regulations and administrative provisions necessary to comply with this Directive at the latest by 27 November 2018.

Table 9 below contains examples of elements described in the Cen Core Invoice data model.

| Element Name | Rationale and use |

|---|---|

Seller Name |

A Core Invoice must contain the name of the seller. |

Seller address line1 |

A Core Invoice must contain the seller’s street name and number or P.O.box. |

Delivery date |

A Core Invoice may contain the actual delivery date on which goods or consignments are delivered from the seller. Also applicable for service completion date. |

Paid amounts |

A Core Invoice may contain the sum of all prepaid amounts that must be deducted from the payment of this invoice. For fully paid invoices (cash or card) this amount equals the invoice total. The CEN Core Invoice model could be invaluable to the ePO as a source of complete and accurate invoice data. |

4.2.1. e-Certis data model

e-Certis is a free online source of information to help companies and contracting authorities deal with the different forms of documentary evidence required in cross-border tenders for public contracts. e-Certis presents the different certificates frequently requested in procurement procedures across the EU [_18]. In particular, e-Certis can help companies to find out which certificates issued in their country they need to include in tender files submitted to an authority in any partner country, or contracting authorities to establish which documents issued by a partner country to confirm the eligibility of a tender are equivalent to the certificates they themselves require.

e-Certis is a reference tool and not a service of legal advice. The information contained in the database is provided by the national authorities and updated on a regular basis [_19].

e-Certis describes the documents using the following metadata:

-

Document type set, e.g. “Certificate required to participate in public procurements”;

-

Document type, e.g. “Proof of tender’s identity”, “Invoices from the service provider”;

-

Country; and

-

Available language.

e-Certis has a high reusability potential for our project as it could be a valuable reference when creating the classes and properties describing the certificates that are needed in the procurement process.

4.2.2. ISA Core Vocabularies

The ISA Core Vocabularies were created in collaboration with and by international working groups facilitated by the Interoperability Solutions for European Public Administrations (ISA) Programme of the European Union . Their aim is to facilitate the exchange of information in the context of European Public Services and address interoperability problems such as the lack of commonly agreed data models and universal reference data.

Core Vocabularies are simplified, re-usable and extensible data models that capture the fundamental characteristics of an entity in a context-neutral fashion. Public administrations can use and extend the Core Vocabularies in the following contexts [_20]:

-

Development of new systems: the Core Vocabularies can be used as a default starting point for designing the conceptual and logical data models in newly developed information systems.

-

Information exchange between systems: the Core Vocabularies can become the basis of a context-specific data model used to exchange data among existing information systems.

-

Data integration: the Core Vocabularies can be used to integrate data that comes from disparate data sources and create a data mesh-up.

-

Open data publishing: the Core Vocabularies can be used as the foundation of a common export format for data in base registries like cadastres, business registers, and public service portals.

Currently available vocabularies are:

-

Core Person vocabulary: captures the fundamental characteristics of a person, e.g. the name, the gender, the date of birth, the location.

-

Core Public Service vocabulary: captures the fundamental characteristics of a service offered by public administration.

-

Core Business vocabulary: captures the fundamental characteristics of a legal entity (e.g. its identifier, activities) which is created through a formal registration process, typically in a national or regional register.

-

*Core Public Organization vocabulary: captures the fundamental characteristics of public organizations in the European Union.

-

Core Location vocabulary: captures the fundamental characteristics of a location, represented as an address, a geographic name or a geometry.

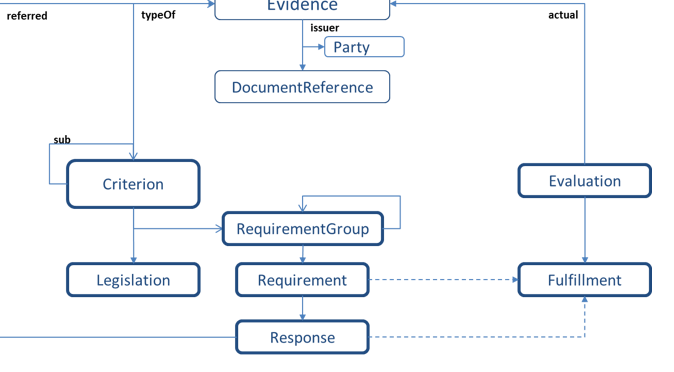

-

Core Criterion & Core Evidence vocabulary: describes the principles and means that a private entity must fulfil in order to be qualified to perform public services.

Of the above vocabularies, the Core Criterion & Core Evidence, Core Business, Core Public Organization, and Core Person vocabularies can be especially useful for the eProcurement ontology as they describe fundamental parties and elements of public procurement contracts. Also, The Core Location vocabulary can provide a solution for describing any location data needed.

| Vocabulary | Class | Description |

|---|---|---|

Core Criterion & Core Evidence |

Criterion |

A rule or principle that is used to judge, evaluate or test something. |

Core Criterion & Core Evidence |

Evidence |

The Evidence class contains information that proves that a criterion requirement exists or is true, in particular an evidence is used to prove that a specific criterion is met. |

Core Public Organization |

Public Organization |

The Public Organization class represents the organization. One organization may comprise several sub-organizations and any organization may have one or more organizational units. |

Core Business |

Legal Entity |

Represents a business that is legally registered. |

Core Business |

Identifier |

The Identifier class represents any identifier issued by any authority, whether a government agency or not. |

4.2.3. The Public Procurement Ontology

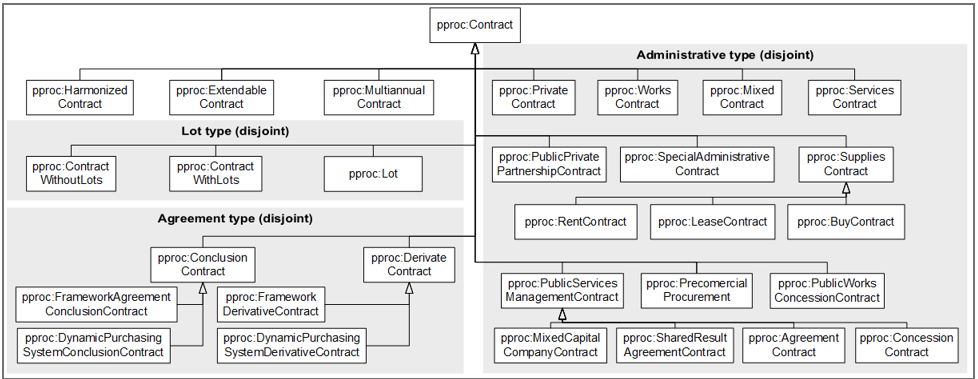

The PPROC ontology has been developed under the Public Procurement Optimization through Semantic Technologies Project (CONTSEM). This project is jointly undertaken by iASoft, the University of Zaragoza, ARAID (Government Agency of Aragon), the Government of Aragón, the Provincial Council of Huesca, and the town halls of Huesca and Zaragoza. The main purpose of the project is to add semantic technologies to the software used by public authorities for procurement procedures to publish data about public contracts. More specifically, one of the core objectives is to describe, semantically, the information published in official procurement bulletins [_21]. CONTSEM participants developed the PPROC ontology in accordance with Spanish laws and European laws in general.

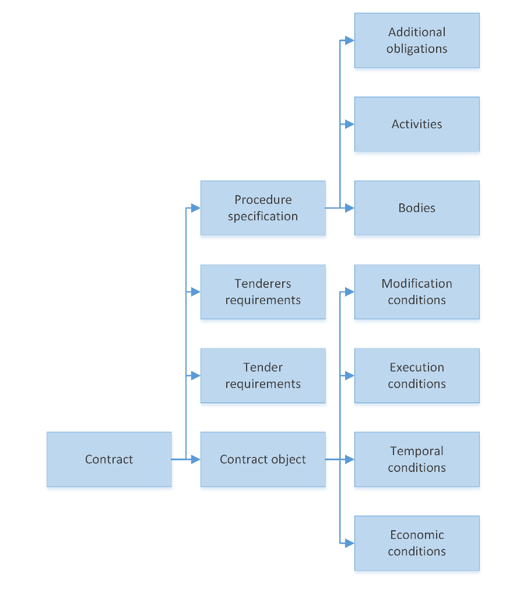

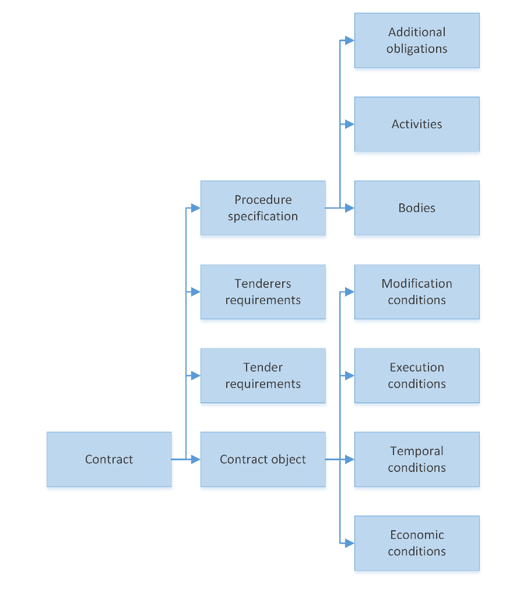

The PPROC ontology defines the necessary concepts needed to describe the public procurement process and its contracts by effectively extending the Public Contracts Ontology. The main Class of the PPROC ontology is the pproc:Contract class, as the contract is considered to be the core concept of every procurement, as represented in Figure 3.

The other core Classes of the ontology which describe different aspects of procurement are the following represented in Figure 4: core classes of PPROC [21].

To describe all other concepts relevant to procurement contracts, the ontology reuses various ontologies and schemes. For example, the following solutions are reused: the Organization Ontology, the Schema.org scheme, the Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS) ontology, the Good Relations Ontology, and the Dublin Core Metadata terms scheme.

The PPROC ontology examined as a possibility for reuse in the ePO as it is extensive in its coverage, compatible with European procurement processes, well documented, and already extensively reuses existing established vocabularies.

4.2.4. LOTED2

LOTED (Linked Open Tenders Electronic Daily) is an ontology for the representation of European public procurement notices developed by the Knowledge Media Institute of the Open University.

It was created following the initiatives around the creation of linked data-compliant representations of information regarding tender notices in Europe, with the aim of addressing a specific problem plaguing previous efforts. Until now projects developing legal ontologies have attempted to represent the legal concepts and the case-based reasoning behind them in linked data simply by mapping them in OWL. However, due to the high level of detail and the nuances of legal reasoning, this approach resulted in extremely complex vocabularies. Complexity is unwanted in semantic applications because for intelligence to arise from linking heterogeneous data, the datasets in question must be flexible enough to integrate effectively.

The LOTED2 model seeks to find a balance between accurately representing the complex legal concepts and the reasoning behind them, and retaining the usability required for semantic applications. [_22]

Specifically LOTED2 has been designed for the following purposes:

-

to express the main legal concepts of the domain of public contracts notices as defined in legal sources (e.g. European Directives on public contracts);

-

to support rich semantic annotation, indexing, search and retrieval of tenders documents, such as contract notices;

-

to enable the integration with other ontologies and vocabularies about related domains; and

-

to make the reuse of semi structured data extracted from the TED system possible, as shown in Figure 5 Semi-Structured data extracted from TED.

LOTED2 is organized into the following 10 independent and reusable core modules which collectively represent 180 Classes:

-

Loted2-core module: acts as the framework for the other modules;

-

Procurements Subjective Scope module: describes the classes of legal persons who are empowered to issue a tender notice (e.g. contracting authorities, contracting entities);

-

Tender Documents module: this module provides a full description of tender documents (e.g. The majority of tender documents available on the TED system are described following this structure);

-

Procurement Regulation module: this module describes the legislative sources regulating public procurement domain;

-

Procurement Competitive Process module: this module describes the competitive process of the procurement (e.g. type of competition, qualification process, award procedure);

-

Subjective Legal Situations module: this module describes the roles played by agents in the procurement process (e.g. role of the tenderer, role of the awarding legal entity);

-

Proposed Contract module: this module describes the details of the contract to be awarded;

-

Tender Bid module: this module describes the tender bid;

-

Business Entity module: this module describes the entities to whom the invitation to submit an offer for a proposed public contract is addressed; and

-

Top module: this module contains abstract classes used to integrate LOTED2 with other core legal ontologies.

In the case of ePO, the LOTED2 vocabulary could be useful as a means of enriching the data represented by the ePO with legal context. Also helpful is the fact that it is already designed with compatibility with TED data in mind.

4.3. The Linked Open Economy ontology

The Linked Open Economy (LOE) ontology was developed for the purposes of the EU funded project YourDataStories.eu. It was created to address the problem of the poor quality of open economic data becoming available as more governments around the world open their data to the public.

The Linked Open Economy ontology is a top-level, generic conceptualization that aims to enrich and interlink the publicly available economic open data by modelling the flows incorporated in public procurement along with the market process to address complex policy issues.

The Linked Open Economy approach is a simple scalable model designed to describe data ranging from public procurement, budgets and spending to market prices. As such it can be easily tailored to a multitude of individual project needs. It also extensively uses existing vocabularies to make integration of heterogeneous data easier.

Table 11 in annex 7.1 summarizes Classes of the LOE ontology as used in the YourDataStories project .

The Linked Open Economy model is an interesting case to look into for reuse as it is quite generic could prove useful, depending on whether it can be tailored to the needs of the ePO.

4.4. Payments ontology

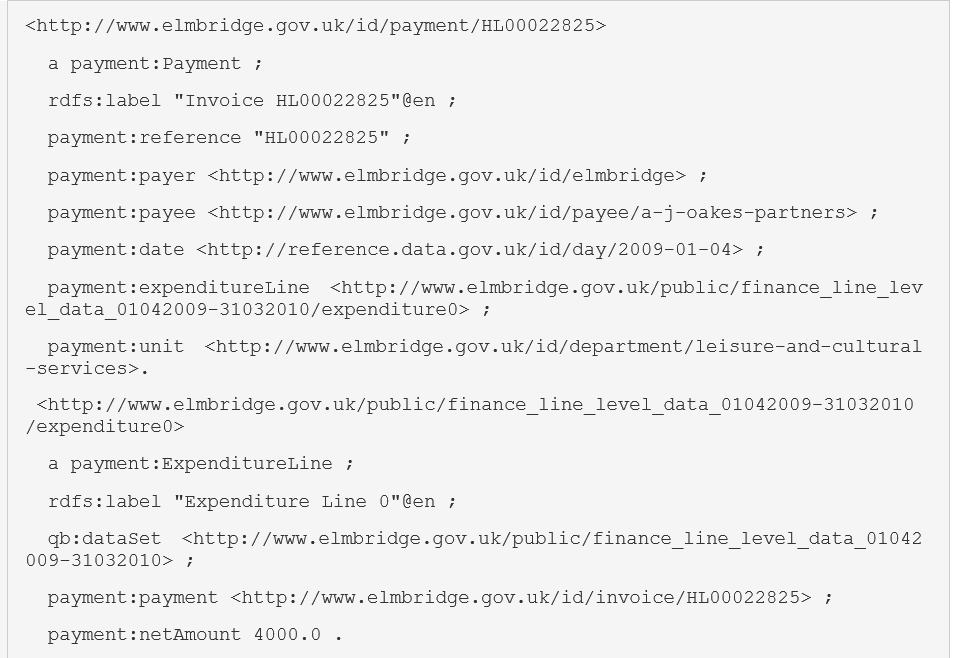

The Payments ontology was created in 2010 by the Local eGovernment Standards Body and the Local Government Group as a part of the UK government’s transparency drive, which requested that all UK local authorities publish detailed information on their spending. The Payments ontology is a general purpose vocabulary for publishing organizational spending data. It is built on the Data Cube vocabulary and represents payment data, which is typically described as a multi-dimensional table. The main concept of the ontology is that of a Payment, which is associated with a Payer, a Payee and a Date. The ontology then provides a number of optional properties to further describe the payment, such as the specific government department responsible or related expenditure line, and to structure the data Cube according to needs.

The following is an example of a payment:Payment instance:

The Payments Ontology can be considered for reuse in the post award stage of the procurement process to model the spending. Its suitability should be discussed however, as it is based on the Data Cube vocabulary, which although suitable for specific kinds of analysis, may prove less than ideal for integration with the rest of the data, as it may be modelled in a different format.

4.4.1. Paraguayan procurement ontology

The DNCP (National Public Procurement Portal) of open data, set up by the government, was created to provide access to data of public procurement in Paraguay and promote the development of creative tools that were attractiveof and service citizens. This initiative aimed to promote transparency, efficiency, citizen participation, and economic development by exposing the work done in various institutions, showing how they are managed and how they invest public resources. Table 12 in annex 7.2 lists all Classes used in the Paraguayan Procurement Ontology. Although the Paraguayan Procurement ontology aims to serve a similar purpose as the ePO, two problems with regards to its reuse were identified. First, the Paraguayan Procurement ontology is modelled completely in Spanish, which limits its reusability in the multilingual EU context. Secondly, the ontology is tailored to the local process. However the ideas behind the ontology could provide an interesting insight.

4.4.2. SEDIA

The Single Electronic Data Interchange Area (SEDIA) is a major strategic initiative that aims to create a master data repository of external stakeholders making business with the European Commission, whether business means grants or tenders.

The goal of the SEDIA project to create a fully automated and integrated process for handling procurement and grants information, strictly limiting the manual input of data to a minimum, and promoting the alignment and reuse of such data along the whole process. This requires the implementation of solutions based on interoperability of the different systems.

This is a process where the actors would not have to submit recurrent information over and over again, but would allow reuse of information previously submitted. Each piece of data that needs to be dealt with should be encoded only once, and then reused or updated according to the needs.

In order to achieve the envisaged interoperability a basic common understanding of the data dealt with is required. Therefore a common data model is to be created.

The SEDIA vocabulary is currently a work in progress. It started by mapping all relevant existing vocabularies and standards to ensure that it achieves its envisioned interoperability, and is in the process of creating a vocabulary.

In this vocabulary we describe all concepts that are part of the procurement process, and whose attributes are relatively static over time, as this is a vocabulary aiming to underpin a repository of stakeholders. Examples of such information are business and organization addresses, names, formal IDs, banking details etc.

The SEDIA vocabulary could be reused in the ePO to represent details about all kinds of stakeholders of the procurement process.

4.4.3. Common Data Model (CDM) of the Publications Office

The Common Data Model (CDM) is the metadata model of the resources published by the Publications Office of the EU. The model is based on the FRBR model, being able to represent the relationships between the resource types managed by the Publications Office. Initially the focus was on metadata related to legal resources and general publications. in a later phase metadata for TED and CORDIS were added. The CDM includes different classes and properties that relate to e-Procurement . The CDM wiki explains which classes and properties are defined in the CDM and how they relate to each other. For example, the CDM defines a Public Procurement class as any of the works related to public procurement (Ted). The model also defines a Prior Information Notice class as a subclass of Public Procurement. The Public Procurement has, among others, the following properties:

-

Submission date;

-

NUTS original reference;

-

CPV original title;

-

eTendering URL;

-

Document number in the Official Journal;

-

Directive name;

Besides defining classes and properties, the CDM also defines relationships between concepts, such as:

-

Public procurement has original CPV concept;

-

Public procurement has current CPV concept;

-

Public procurement value expressed in a given currency;

-

Public procurement notice published in official journal;

The CDM can help us understand how different metadata concepts of e-Procurement relate to each other. The ePO will respect the naming and design rules of the CDM. Moreover, as the CDM is available in OWL, its elements can be reused by the e-Procurement Ontology wherever possible.

4.4.4. Standard forms for public procurement (TED)

Following the adoption of the revised e-Procurement Directives, a new set of standard forms for public procurement was introduced. With the new directives, the forms are meant to be used in an electronic format only, which allows for automatic checking of mandatory fields. Moreover, the clear structure of electronic notices ensure consistency with the European Directives and minimize the risk of encoding errors. The forms, which are available via SIMAP, impose a structure for submitting the following information:

-

Prior information notice;

-

Contract notice;

-

Contract award notice;

-

Periodic indicative notice - utilities;

-

Contract notice - utilities;

-

Contract award notice - utilities;

-

Qualification system - utilities;

-

Notice on a buyer profile;

-

Design contest notice;

-

Results of design contest;

-

Notice for changes or additional information;

-

Voluntary ex ante transparency notice;

-

Modification notice;

-

Social and other specific services - public contracts;

-

Social and other specific services - utilities; and

-

Social and other specific services - concessions.

The standard forms for public procurement are very important for the development of the ePO as they describe how public procurement data should be submitted for publication in order to comply with the public procurement directives. Since the ePO has to be compliant with the same directives, it should take into account the concepts, data structure and controlled vocabularies of the standard forms for public procurement. Moreover, in 2015, the Publications Office and the ISA Programme of the EU conducted a study to elicit information and functional requirements from TED reusers [_23]. The requirements identified by this study could be considered when developing the ePO.

4.4.5. Other generic vocabularies that should be taken into consideration

| Vocabulary | Descriptions |

|---|---|

FOAF |

FOAF (Friend Of A Friend) is a vocabulary defining a dictionary of people-related terms that can be used in structured data |

Dublin Core Terms |

The Dublin Core Terms is a set of vocabulary terms that can be used to describe web resources (video, images, web pages, etc.), as well as physical resources such as books or CDs, and objects like artworks. |

SKOS Core |

SKOS Core is a model and an RDF vocabulary for expressing the basic structure and content of concept schemes such as thesauri, classification schemes, subject heading lists, taxonomies, 'folksonomies', other types of controlled vocabulary, and also concept schemes embedded in glossaries and terminologies. |

4.5. Reference data and code lists

4.5.1. The Common Procurement Vocabulary

The Common Procurement Vocabulary (CPV) was created by the European Commission in order to facilitate the processing of invitations to tenders published in the Official Journal of the EU by means of a single classification system to describe the subject matter of public contracts. This classification endeavours to cover all requirements for supplies, works and services [_24].

The CPV consists of a main vocabulary for defining the subject of a contract, and a supplementary vocabulary for adding further qualitative information. The main vocabulary is based on a tree structure comprising of codes of up to nine digits associated with a wording that describes the supplies, works, or services forming the subject of the contract.

For example, if a contracting entity wants to obtain a road transport service for a fragile high-tech device, it may be interested in looking into the following codes:

-

60100000-9 Road transport services

-

60110000-6 Public road transport services

Another example could be if an entity is interested in buying general-purpose rolling machines and parts for them. In order to find the most suitable codes, it could look into the following codes:

-

42000000-6 Industrial machinery

-

42930000-4 Centrifuges, calendering or vending machines

The supplementary vocabulary may be used to expand the description of the subject of a contract. The items are made up of an alphanumeric code with a corresponding wording allowing further details to be added regarding the specific nature or destination of the goods to be purchased.

For example, specific metals may be designated with the supplementary vocabulary codes: AA08-2 (Tin) or AA09-5 (Zinc).

The use of the CPV is mandatory for all public procurement procedures in the European Union as from 1 February 2006 [_25].

The CPV should be used in the case of the ePO as it is obligatory by directive. Furthermore as it is a wide spread and well established standard, its inclusion will facilitate integration and reuse of published data. An update of these CPVs are also foreseen within the ISA action: European Public Procurement Interoperability Initiative which also covers the ePO.

4.5.2. The Named Authority Lists of the Publications Office

The Named Authority Lists (NALs) are harmonised code lists with multilingual labels used to facilitate data exchange. They are maintained by the Publications Office of the European Union in the Metadata Registry under the governance of the EU’s Interinstitutional Metadata Maintenance Committee (IMMC).

The use of common, high-quality reference data in information reuse can significantly reduce semantic interoperability conflicts. Available in different machine-readable formats and maintained by a trusted authority, the NALs can be reused in many different information exchange contexts.

Some examples of NALs that could be used in the domain of e-Procurement are those on countries, currencies, documentation types, EU programmes and EU corporate bodies [_26].

4.5.3. Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics

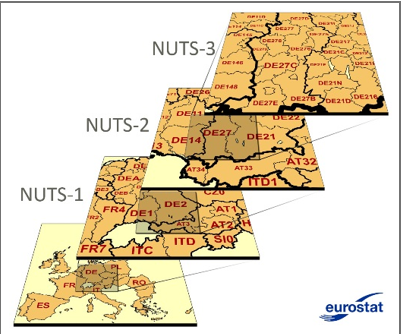

The Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS), is a geographical nomenclature subdividing the economic territory of the European Union into regions at three different levels: NUTS 1, 2 and 3 respectively, moving from larger to smaller territorial units, as it is shown in Figure 6.